How Does It Feel to Have a Missing Family Member

I t was vii.40 on a Lord's day night when 16-year-old Kevin Hicks popped out to the local shop. He had a cookery test the next day, and the family had used up all the eggs making yorkshire pudding for supper. The shop was a short walk – yous could see information technology from his bedroom. Kevin left dwelling house with £i, and told his female parent he'd be back in a few minutes. That was 29 years ago.

On the mantelpiece of a dark, winter-lit room in Croydon, s London, there is a photo of a handsome boy looking ahead to life. "That was taken iii weeks before Kevin went missing," his sis Alex says. Her home is full of mementoes: his favourite cassettes (Madness, Survivor, Nihon, Yazoo); the jumper he is wearing in the photo; his Co-op uniform; his Crystal Palace scarf.

Alex was 14 when Kevin went missing, and for years she wanted nothing to do with the campaign to notice her brother. She left that to her parents. Simply now they are both gone: they died prematurely, heartbroken – her mother aged 47, her father at 57. "My mum did an appeal a week before she died. They never gave up looking. I don't feel I accept to do it – I want to practise information technology. They didn't get answers. Hopefully I can. If he comes home, the first affair he'll get is a slap." She laughs. "All the grief he's put us through. Then he might just become a hug."

When someone goes missing, it is usually, understandably, the parents who are forced into the spotlight – the ones who do the constabulary press conferences, the ones who campaign, the people around whom public sympathy gathers. Only how does it experience for the brothers or sisters left backside? Often young, they are relatively powerless; they don't go to make up one's mind what happens next, or how the family is going to deal with the trauma. A grieving parent might stifle them with love or worry or both; a grieving parent can shut them out completely. Information technology is common for the sibling of a missing person to experience terrible survivor'due south guilt, and to later projection their parents' anxieties on to their own children.

Alex remembers very clearly the night Kevin went missing: her female parent looking out the upstairs window all night long; her anger at having to get to school the next morning when Kevin was away, messing virtually; the fact that but boys could assistance look for him, in case they plant something terrible; the police officer who took her aside and suggested she knew where Kevin was, and that if she told him she wouldn't go into trouble. They were not allowed to report him missing until he'd been gone 24 hours, considering he was sixteen and classed as an adult. "Now, all that has inverse. As soon as y'all know someone is missing y'all can report it."

Past the end of the week, Alex was distraught. Kevin had never run away and had no history of mental illness. "I began to think somebody had taken him. He wouldn't walk off – that wasn't him." The police have never plant any trace: nobody saw Kevin that night, there were no CCTV cameras and there have been no reported sightings since.

The family started to receive foreign calls. "The first seven or eight months, the telephone would ring and there'd be no one on the end of it. Dorsum then, yous couldn't do 1471 or withhold your number. Information technology would ring and ring, then when y'all picked up, information technology would exist silent. We'd say, 'Kevin, if that's you, say something.' I'd say, 'Kevin, if you don't want to come home, come across me at the park after school.' That was always the time I walked the domestic dog."

The calls connected for a couple of years. Her mother got them at C&A, where she worked. "She only worked Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday mornings, and that'south when they came."

Alex became more convinced Kevin was live after her mother died. At the funeral, she and her father counted the bunches of flowers that had been left. The next day, there was an extra agglomeration. "I think Kevin put them there. That church was packed. He could have been there, listening."

His disappearance almost destroyed her relationship with her parents. "They wrapped me in cotton wool. I couldn't breathe. I wanted to get out, have a life, and I started to kick off. 'I want to see my friends, this isn't fair. You tin't keep me like a prisoner.' I said some hurtful stuff." Like what? "This is all Kevin's fault – if he'd just come home, I wouldn't exist treated like this." At 16 she moved in with a friend. "I couldn't handle it whatsoever more. They were wrapping me upward, tighter and tighter." She and her mother didn't speak for nearly a year.

Past 21, she was married with two daughters, who have grown up waiting for uncle Kevin to come abode. "They know he was a footling sod. He had a magic box and you'd sit down and the whoopee absorber would become. They know and so much about him, they want to run into him face-to-face." Alex segues between present and past tenses.

Does she understand now why her mother became so protective? "Oh God, aye. If I tin can't go concur of my kids on the telephone, I'm going ballistic."

On a adieu, she likes to think Kevin joined the military machine. "Army or navy, on the chefs' side. I simply have that inkling." The longer y'all have been away from home, she points out, the harder it becomes to go far touch, even when you want to.

Does a day pass without thinking nigh Kevin? "No. I piece of work in Sainsbury'southward, I could serve him and not realise. I could be at a hospital appointment and he could be sitting next to me. I'one thousand fighting for Kevin to be on Crimewatch, only they can't do a reconstruction because at that place's nil to bear witness. All they tin can do is motion picture upward the route where he was heading, to the shop that is no longer at that place."

I ask why she is so convinced Kevin left of his own accordance, and her face collapses. Information technology'southward obvious the alternative doesn't bear thinking about. "Over the years I've talked to psychics and mediums," she says. "A few have said he got taken that night. He got pally with an older guy, racing his remote-command car at Ashburton Park. They say this guy said, 'I've lost the dog, Kevin. Can you help me?' Kevin was animal mad, and so he'd say no problem. Three mediums have said that. Others have said they can gustatory modality water, which is a sign of drowning."

Through the charity Missing People, Alex has met many other families who have gone through similar experiences, and she encourages them to exist positive. "When my parents went looking for Kevin, they always looked up, not downward. They got pally with the parents of another male child and they were very negative, e'er looking downward under bushes. Mum convinced them to have this little bit of promise. 'You ever have to look up,' she'd say."

We oft come across images of missing people – in the Big Issue, on police force station noticeboards, on scraps of paper stuck to copse. And we often assume they are outsiders: addicts or alcoholics, people who have flunked the game of life. But missing people come from all over. An estimated 216,000 people were reported missing in the UK in 2010-xi, according to Missing People'south nearly recent figures, and an estimated 250,000 go missing every year. Home Part statistics reveal that more than half of those are under eighteen. Most cases are chop-chop resolved: in 2011, 91% were closed within 48 hours. An estimated 99% are solved within a year. But that still leaves around 2,500 people who go missing every year and get out no trace.

It is 20 years since Richard Edwards' machine was establish abandoned well-nigh the Severn bridge. Richard, meliorate known as Richey, was a member of Manic Street Preachers, the most tortured and idolised. He was the guitarist who couldn't play guitar, the skinny boy in eyeliner who cut himself (famously etching four Existent into his arm during an interview with NME).

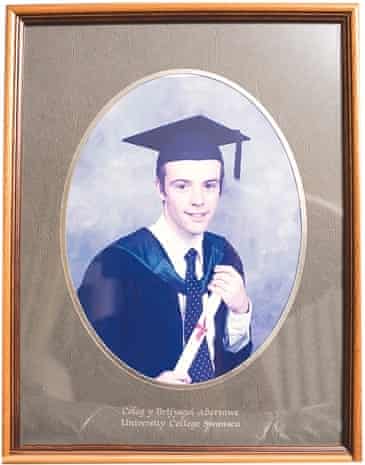

I run across his sister Rachel Elias at her mother's bungalow in Blackwood, a former mining town in south Wales. Rachel lives down the route, only spends lots of time hither with her mother. In a small room off the kitchen, there is a photograph of Richard (Rachel e'er calls him Richard) receiving his English caste – immature, hopeful, not very stone'n'coil. Next to it is a pile of old 45s, some hers, some his – the Smiths, Scott Walker.

Rachel, 45, is a small, striking adult female. You don't need to look hard to see Richard in her. Her memories of him are random, lingering. "Ane of the last matches he watched on idiot box was Newcastle v Blackburn. I don't know why I recall him telling me that. A few weeks before he went missing, our dog died, a Welsh springer spaniel." They were both living in Cardiff, where Richard had bought a apartment. "We came back home, bought a tree from B&Q and buried the dog."

Richard, two years older than Rachel, was a smart, artistic boy, who would help her with her homework. In the years before he went missing, he suffered astute depression; he had simply recently come out of the Priory afterwards a previous stay at Whitchurch psychiatric infirmary in Cardiff. Rachel didn't think he was troubled as a teenager, just looking back she tin can meet signs. "He used to pick up a compass and do this." She scrapes herself with an imaginary compass. "He wouldn't exercise it in forepart of me. But I knew. I never said anything."

She visited him in infirmary and by now he was seriously self-harming. "I'd say, look at your wrists. He'd say, that's nothing compared to the mental pain I feel. I of the nurses gave him a book past Spike Milligan, Depression And How To Survive It. Milligan said he was then sensitive to things, he felt skinless – I think Richard identified with that." Did the music business make things worse? "Who knows? Those symptoms might have manifested themselves if he'd been working in a bank."

She thinks the Priory made him feel special, which she hated – as if his depression was a gift. "You were treated like a pop star. A psychiatrist told my mother he was the Richard Burton of the music world. I thought, what? Because he was Welsh?" Eric Clapton was an occasional counsellor there. "I idea it was funny he and Richard exchanged CDs. He gave him From The Cradle, his blues album. Richard couldn't even play guitar."

Richard had told her he wanted to leave the ring and only write lyrics for them. But in the finish he agreed to a US tour to promote their third album, The Holy Bible. On 31 January 1995, he and ring mate James Dean Bradfield checked into the Embassy hotel in London, ahead of their flight. The next morn, when Bradfield knocked on his door, there was no answer. Staff plant the room empty except for a few personal items. A fortnight afterwards, Richard's silver Vauxhall Cavalier was found at the Severn View service station. The Severn bridge was a renowned suicide location – but a lock had been fitted to the steering wheel, which made the family think Richard had been planning to return.

His disappearance was entirely out of character. "He took his responsibilities seriously, and he'd fabricated the decision to render to the ring. He used to ring my mum and dad every day, so just deserting them, not making the flight… "

Rachel knows how many people go missing, but says it'due south an isolating experience: "Other people don't know what to say to you or how to treat you." Over the years, she has found comfort through Missing People. On her mother'south mantelpiece, there are framed pictures of families. I ask who they are. "Other families with missing people," Rachel says. "They take become friends."

There have been numerous conspiracy theories about Richard's disappearance, including the proposition he was targeted by government agents because he wrote a vocal called If White America Told The Truth For One 24-hour interval Its World Would Fall Apart. But Rachel is non interested in speculation – she only wants the facts. She has campaigned to get the families of missing people one single point of police contact (there were three forces involved in the search for her blood brother) and has fought for the DNA of missing people to be cross-matched with Britain's database of more than than 1,000 unidentified bodies: "About people simply don't know about the database." It took 10 years to get Dna from Richard's hairbrush tested. No lucifer was found.

For a while later he went missing, Rachel would drive effectually at night, looking for him in their old haunts. Then she stopped, thinking it pointless. Twelve years ago, she took a job in a night shelter for homeless people. She never questioned why, then realised she was looking for Richard. "He'd shaved his head and had a bobble chapeau on before he went missing. And sometimes I'd walk past the living room, run into the shape of someone and call up…"

She has become less rose-tinted about the world, less secure. "If you go to the Missing People office, at that place is a wall of grainy photographs. You think you lot live in a safety world, then you lot see that and retrieve, no, no. It makes everything seem more sinister."

Seven years later on someone has disappeared, they can exist alleged dead in absentia. The family decided against this initially, but in 2008, thirteen years after Richard went missing, they agreed it would exist the best course. Their parents were getting older, and they still had Richard'south bills to pay. His father, who has since died, told Rachel and her mother he didn't want to exit them with these worries. "And then nosotros wound up his financial diplomacy. Until then we were going downward to look after his flat."

Merely it was not a unproblematic process. Insurance companies often challenge a case, because they believe families might exist on the make. "I had to go in front of the judge and swear on adjuration that I believe he is dead. That was a very hard feel. I wrote the affidavit. We had to build up this picture almost why nosotros thought he may have died, bear witness his psychiatric history, how it was out of character, what effort we fabricated to locate him. I've met families since who have had multiple applications rejected. Our starting time was. We had to add more than data, then the judge just stamped it." Tin can she call up the mean solar day they got the certificate? "It merely came through. 'Richard Edwards deceased.' Yeah, that was hard to read."

There is nonetheless no sense of closure. Does it become easier as the years go by? "Well, recently I've come to organized religion and I go to church. One of the hardest things is that my dad died not knowing. Sometimes I think, well, you accept to face the possibility that you may have to live with this uncertainty." She pauses. "But I recollect at some signal, if not in this life, information technology will be revealed. And I will know."

Donna Davidson imagines the best possible scenario for her brother Sandy. "I'd like to think he was taken by a family who couldn't have children, and they've brought him up well." She stops abruptly. "Only I don't think that is the instance, so I'd prefer he was dead. I'd similar to recall it happened quick and he didn't suffer with a paedophile. I definitely think he was abducted and killed."

It is 39 years since Sandy went missing. He was 4 and playing in his grandma's garden in Irvine, Scotland. Donna, who was two, was with him, though she can't think it. Despite the motion-picture show of the gorgeous little boy with the Shirley Temple locks, she has no memories of him: "That hurts."

These days she lives by the sea in Saltcoats, Ayrshire. She has 3 children, recently became a grandmother, and works as a barmaid. Inquire anybody, she says, and they'll tell you she'south the life and soul of the pub. "But it's all a front. You learn to deal with it. I wouldn't wish this life on anybody – just not knowing what happened."

Like so many others, her parents dealt with Sandy's disappearance by not talking virtually information technology. "Nobody mentioned his name. You weren't allowed to expect at pictures." Her father would disappear on Sandy's birthday. When she had her own children, the memories came back. "When my youngest male child was four, he looked but like him. And my mum said, get his pilus cut off, because he had a mass of curls. He was his double. I said, he'due south not getting his pilus cutting. Yous need to get over it."

Did they ever want Sandy declared dead, like Richard Edwards' family? "No. Even though I think he'due south expressionless, I wouldn't like that, no. Until we notice the trunk, there's always that bit of hope."

Throughout her childhood, her mother worried badly for her and her younger brother's safety. Now, Donna says, she's the same with her ain children. "I've been overprotective to my kids. The youngest, who'south 15 and Sandy'south spitting image, is a horror. You never know where he is. Whenever my kids go out, my stomach's in knots."

"I miss the conversations we had. I can't take those with anyone else. I miss his sense of sense of humor, his music – he had an amazing voice. I miss his confront."

Ben Moore is talking virtually his brother Tom, who went missing xiii years ago, aged 31. Ben, a curator and pic-maker, is seven years younger. We meet in a guild in Soho, London, i that began life equally a refuge for homeless women in Victorian times. Ben has a bohemian air: well spoken, long hair, chiselled cheeks, slightly tortured demeanour.

When Ben was growing up, Tom was his hero. "I was in awe of him. He liked to play guitar, he had absurd friends." Then he started taking drugs and becoming "weird". Ben feels guilty: rather than trying to sympathize, in his early on 20s he pushed Tom away. "At that age, all you tin can retrieve of is trying to tick boxes to exist cool, right? And if the boxes aren't matching, you're not interested."

The brothers grew up in a well-to-do family unit in west London, with some other brother and a sister. Their father had been a colonel in the Imperial Marines; now both parents teach English language. Tom studied theology at Lancaster Academy, and so went to India to find himself, working with the poor and spending time with Female parent Teresa ("He wasn't her right-hand human being or annihilation"). He took mind-altering drugs, and was never the same once more. "Requite him a drop of anything and he'd twist it into some terrible nightmare. He was religious and there is a lot of fear as well as promise in religion – he got caught upward in a paranoid, twisted puzzle."

Back home, he was put on antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs. "He was on olanzapine, which basically shuts downwards your mind. Zombie powder. He'd be on it, then come up off it, and that's when it's dangerous. Suddenly you're allowed to breathe, you lot're awake for three days, and boom!"

Over a period of years, Tom got meliorate. He was never well, but he was calmer. Then i 24-hour interval Mormon evangelists knocked on the door, and he let them in. He became a Mormon, while too embracing his Catholicism. Aged xxx, he decided to go travelling again, often to spiritual landmarks and usually without warning. Invariably, there would be a mishap. He was mugged in Paris. He went for a swim in Cannes and somebody stole his apparel. He stowed abroad on a ship to Corsica, just was discovered and returned to France. His uncle had to rescue him from a hostel in New York.

More oftentimes, it was Ben who would fetch him. He started to make a film about Tom. One time he disappeared and was discovered in Medjugorje, Bosnia, a site of Christian pilgrimage after local children said they had seen the Virgin Mary. "He was there for a month. I managed to bring him abode, but I was questioning why I was. I was only doing it under orders from our parents."

Ben is convinced his brother is still alive, and is the nigh optimistic sibling I speak to – because Tom had a history of disappearing. For Ben, it is a case of when, not if. He believes Tom was in Ancona, Italy, on xx July 2003, considering his banking concern card was used to withdraw a small amount of greenbacks. Since so Tom's card has not been used, simply every few months Ben hears of a potential sighting. He shows me a photograph of a man in Italy. He'south red-haired, bearded, craggy, a good Tom lookalike. "What d'yous recollect?" he asks. Well, I say, information technology does look like him, but lots of people expect like Tom. "No," he says, momentarily deflated, "it's non him. I've got to go with my gut. And when I first saw information technology, my whole existence went, 'Nah.' Seeing your brother, it would but be: 'Blast!'"

Like Rachel Elias, his brother'southward disappearance has given him faith. He says he'd similar to have his photo taken in the chapel bordering the gild where we meet. "It has strengthened my religion in Catholicism, and my faith that he's around." Ben talks about the day Tom went missing. They were in the center of a game of chess. "I was winning, and he put it on hold. I wish I'd kept the game. I realise at present I was winning considering he was distracted by the mission he was almost to go on. I realise now he'd come round to say goodbye."

At that place is a pattern to Tom's disappearances and Ben takes hope from that. "Tom discovered all these religious cults, sects, when he was travelling. A lot of people within them are registered missing – they get swallowed upward and the years go by. He could be with 1 of them. The only way we'll see him again is me or someone else finding him."

Will Tom be pleased to see him? "Yep, it would exist such an amazing meeting. I mean, wow! For me, that is the holy grail. Information technology's as exciting as that."

He admits he's equally driven past the thought of completing his documentary. He pictures information technology all – the reconciliation, Tom telling his story. "This is a very selfish, vain part of me talking," he says, apologetically. "But I'd beloved to cease that film."

H ow does it experience for the siblings who come back, or are found? Bill Andrews, 57, had a tough babyhood. His mother walked out when he was a niggling boy, leaving him with his father and an calumniating step-mother. He was made a ward of courtroom and spent years in care, often running away to search for his mother. Every bit a young man, things started to expect up: he worked on the docks and married a adult female he loved. Merely later 13 years she left him. He tried to kill himself, and was sectioned. On his release from hospital, he decided to walk away from everything, leaving Rochester and heading for London. He went missing for 12 years, 2 of which were spent on the streets. He was eventually helped past the mental health charity Mind to resettle in Dartford, which is where we talk.

The moment you come across Andrews, you know he'due south a grapheme – friendly, tough-looking, vulnerable. He wears his cap back to front, is known as Bill the Hat, has Millwall tattoos on both forearms; gold football boots and boxing gloves dangle from his neck. His home is small and crammed with family photographs, especially of his second wife Sharon. He says she saved him.

Xi years ago, in June 2004, he received a alphabetic character from the National Missing Persons Helpline:

"Honey Mr Andrews,

We have been asked by [his mother and sis] to try to contact you. We are able to pass on contact details to you, should you wish to be in touch directly. Alternatively nosotros are prepared to pass on any letters and deed as intermediaries."

How did he experience? "I was shocked. I idea, how the hell did they notice me?" Information technology turned out his sister, one of 14 siblings or half-siblings, had moved to Dartford and lived on the same road. She had never seen him, merely had heard he had been spotted locally, then got in touch with the helpline.

"For 2 hours I was walking up and down my flat, pacing and pacing," Andrews says. "Then I rang them, and they got in touch on with my mum. She rang me and said, 'Come up over at the weekend.' I said, 'OK. Are you all the same at the aforementioned identify?'"

I'yard desperate to hear Andrews' feel-good story – the great emotional reconciliation, how he and his female parent defenseless upward on the missing years. But life turns out to be not so obliging. "I'd been missing for 12 years, and at 11.30am she put Sunday dinner on the table. Her famous apple pie and everything. Half eleven, having dinner? I thought, what's going on? And she shoved me off to bingo. I'd been missing for 12 years and she wanted to get to bingo. Seriously! Information technology was unbelievable." He hasn't spoken to his female parent for iii years, though his relationship with his sis is better.

Sometimes he wishes he was still alone, quietly living his 2nd life. But on the whole he is glad to exist reunited, not to the lowest degree because it gives other missing people, and their families, hope. "In that location are so many people crying out for that helping hand. It's a shame they can't prove photographs of missing people every day on boob tube, put out alerts. I do get my bad days…" He stops mid-sentence, and his face lights up. "So I've got my niece ringing upwards: 'Nib, when are you lot coming to see u.s.?'"

He thinks his 12 years missing changed him for the meliorate. Yep, at that place were terrible times – only if he'd never gone missing he would never take met Sharon. He describes how he walked into a dental surgery when he was at a low. He'd broken a crown, and Sharon was working in that location. He read her a poem he'd written and 13 weeks afterwards they were married. Then there are all the people he wouldn't have met if he'd not gone missing. "I started trusting people once again. I used to help people if they had nowhere to stay. They chosen my flat Bill's Caff. They all used to turn up for biscuits and coffee. I had five or half dozen prams outside."

What made him outset trusting people? "I felt people had gone a long manner to assist me. Now I could give something back. If I've got money, I'll lend coin. I'll give them food." This is what gives him nigh satisfaction. "Helping people get stronger. I learned that on the streets."

mcknightmaske1955.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/apr/11/missing-people-brothers-and-sisters-simon-hattenstone

Post a Comment for "How Does It Feel to Have a Missing Family Member"